Ann Berry tells the story of her great uncle, Joe Garstang, from Preston. As a committed socialist and member of the No Conscription Fellowship, Joe took an absolutist stance and refused to have anything to do with the conflict. As a result, he spent several years in prison, during which time he went on hunger strike and was force-fed. Ann’s family believe that this experience broke Joe’s health. A market gardener and fitness instructor before the war, he was unable to return to his former working life when he was released from prison for the last time in 1919 and he died less than 10 years later, aged only 38.

Joseph Garstang: the Absolutist

Posted by Ann Berry

The Journey Begins

I first became aware of Uncle Joe’s existence in 1976. My brother was visiting our dying grandmother in hospital. As he approached her bed, she greeted him with the words, ‘Hello, Joe. I didn’t know you were coming.’ My brother’s name is David, after Joe’s brother, our grandfather, both of whom were long deceased before my brother was born. We later discovered that David is the image of Joe.

Fast forward to 1988 when an article appeared in the Lancashire Evening Post. The headline read ‘Riddle that’s Baffled the N.W. Art World.’ A Preston artist, Patti Mayor, who had died aged 90, had left many unnamed portraits in her collection. The Grundy Gallery in Blackpool were exhibiting her work and were asking for information about her mystery paintings. My father and his cousin had in their possession four paintings by Patti Mayor: two of Uncle Joe, one of our grandfather, David, and one of their sister, Polly. We contacted the Grundy and the four paintings hung in the Gallery for eighteen months. My aunt informed us that our family had been friends with the painter and her sister and that Uncle Joe and Patti had been sweethearts. My father and his cousin have since died so our beautiful paintings now grace our walls.

In 2012 Patti Mayor’s painting, ‘The Half Timer’ was on display at the Harris Museum in Preston and I attended an interesting talk about her life, which gave a good insight into Edwardian life. The curator informed us that Patti was a very private person, never marrying and living with her sister until her death in 1962, so it was interesting that she and my great uncle had been sweethearts earlier in her life. Patti had been involved with the suffrage movement and had attended rallies in London, taking her painting mounted on a stick with the slogan ‘Preston Lasses Mun Hev the Vote.’ Her home was reputed to be an oasis of good talk and cultured entertainment and hopefully a place where Joe and his siblings could meet with their friends.

I was speaking one day to a family member about the paintings of Joe and happened to mention that I had heard that he had been a conscientious objector during World War 1. The reply disturbed me:

‘Your grandma used to talk about him. He was imprisoned and treated really badly. They put him in a straightjacket and shackled him. His health broke and he suffered ill health for the rest of his life.’

This information was given to me about two years ago, so when I heard about the Global Link project in the Lancashire Evening Post, I felt compelled to find out more. I arrived for the first group meeting and was given a sheet of paper with information about Joe that had been compiled by historian, Cyril Pearce, who has researched World War 1 COs. I was informed that the contents of this paper would be upsetting. It was quite a shock to find that a family member had gone through so much for his beliefs.

It was quite a shock to find that a family member had gone through so much for his beliefs.

Joe’s Early Life and Family

Joe was born on 8 October 1888 at 15 Blakehall Street, Preston. His parents were Elisha and Jane and he had an older sister and two younger brothers. Both Joe’s parents worked in the cotton industry, Elisha as a ‘self-acting minder’ or weaver operating a multi-threading spinning machine.

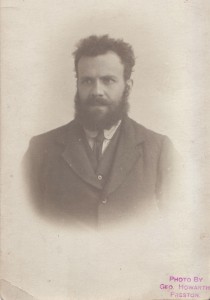

Elisha was quite a character. He was a vegetarian, only eating brown flour. His wife would get family members to smuggle in white bread for her. Elisha was an atheist and an early member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP). He enjoyed reciting poetry and would perform to any interested party.

The family were close knit, affectionate, fiercely independent, had a great sense of humour and enjoyed an outdoor life. By the time of the 1901 census, the family had moved to Church Avenue and Elisha was still cotton spinning but thereafter the family moved to Chain House Farm in Ashton where the boys became market gardeners. They bred chickens, kept dogs and took advantage of their market gardening produce. This was a part-time pursuit for Elisha who was still working in the mills.

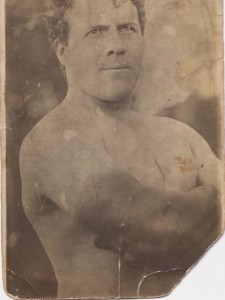

Joe’s War

At the outbreak of war Joe was working as a market gardener and fitness instructor. He was a strong individual. Extremely fit and muscular, he could lift three men at a time.

Joe, like his father, was an atheist and a member of the ILP. He strove to set an example by leading a socialist life, participating in cultural as well as political activities which aimed to establish a society founded on justice and comradeship. The outbreak of war would shatter that dream for Joe.

By the time of his call-up in 1916, Joe had joined the No Conscription Fellowship. [1] As a committed socialist, he saw the war as leading merely to the killing of his fellow workers. Family legend has it that he said of the young men he trained as a fitness instructor, ‘I’m not training these lads up to be cannon fodder.’ I found an undated article about Joe’s father, Elisha, in the Lancashire Daily Post and feel that it’s relevant to say ‘like father, like son’:

‘To know him you must realise that he has great independence of spirit. Elisha Garstang would break rather than bend.’

Joe must have refused to respond to his call up papers, as he was arrested on 16th April 1916 and tried at Preston Magistrates Court where he was fined 40 shillings and handed over to the army. He was assigned to the 3rd Loyal North Lancashire Brigade, based at Felixstowe. Now under army rules, we can assume that Joe continued to refuse to follow military orders, as he was court martialled twice in May and December 1916, being sentenced each time for up to two years with hard labour.

‘I’m not training these lads up to be cannon fodder.’

Joe kept up his resistance in prison. While in Ipswich gaol in January 1917, Joe went on hunger strike for three weeks, during which time he was force fed 38 times and was transferred to Wandsworth Prison hospital. The matter of Joe’s force feeding led to questions in Parliament on 2 April 1917, where Mr William Byles MP asked: ‘whether [Joe’s] health is suffering from this treatment; and why this conscientious objector is denied the protection of the Military Service Act?’ In reply, Sir George Cave said:

‘This man applied to the Central Tribunal and was allowed work under civil control in lieu of military service. Having refused to take up this work in November last he had to go back to the Army and was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for disobeying a lawful command. During the month of January he refused food and had to be forcibly fed, but he was discharged from hospital on 29th January upon his promising to behave normally, and his conduct has since been quite satisfactory.’ [2]

It appears that Joe took an absolutist stance, refusing to have any part in war-related activity and that he experienced a cycle of imprisonment and release, followed by re-arrest for continuing to refuse to follow military orders. Despite apparently ‘promising to behave normally’ Joe was court martialled again in June 1917 and May 1918. In September 1918 he was moved to the Wakefield Prison work camp, under the Home Office Scheme. By January 1919 Joe had served three sentences and spent more than two years in prison. Presumably, Joe was released in 1919 and was able to return home.

‘During the month of January he refused food and had to be forcibly fed, but he was discharged from hospital on 29th January upon his promising to behave normally, and his conduct has since been quite satisfactory.’

Joe’s Return

Like countless other men, Joe returned to a very different world from the one in which he had grown up. He was lucky that he could be with his parents and enjoy the companionship of his now married siblings. His parents had moved to farms in Belthorne and Osbaldestone where his father successfully bred his beloved poultry but, with Joe’s health failing, the family moved to Rufford to a more manageable way of life. However, Joe’s working life was virtually over. He died on 22 August 1928 in the Royal Preston Hospital of septicaemia due to pyorrhoea at the age of 38. I think a description of his father, Elisha, in the Lancashire Daily Post article is a fitting tribute to Joe: ‘His heart was in the countryside, in the wide spaces where a man may breathe the pleasant odour of leaf mould, wet earth or the sweet scent of a thousand flowers.’ Our Great Uncle Joe, I would have loved to have met you. But you are looking across the fields at me, as Patti painted you all those years ago.

- [1] Details of Joe’s experiences as a CO were sourced from Cyril Pearce’s WW1 CO Database.

- [2] Hansard, 2 April 1917. Question about Joseph Garstang. Vol 92. Available at: www.hansard.millbanksystems.com