Catherine Marshall became prominent in suffragist and peace activism, significant national movements in the last century. She was involved in the National Union of Women’s Suffrage (NUWSS) from 1908. She resigned from the NUWSS in March 1915 as the Council of the organisation did not give leave to work for peace in the way that Catherine wished. Whilst still committed to votes for women she considered that working for peace was a more urgent duty for women and from 1915 her focus shifted towards pacifist and socialist activities. She became involved with the No Conscription Fellowship and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. With both of these organisations she took a significant and influential role.

Catherine Marshall (1880-1961): From Suffragist to Peace Activist, Part 2: Peace Activist

Posted by Gail Capstick

Background: shifting from suffrage to peace activism

The suffrage movement had been subject to divisions and factions. The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was no different and in 1915 the First World War divided the Society. Several members of the Executive resigned, questioning the decision to suspend activities to achieve the vote and the patriotic approach that the NUWSS had adopted at the onset of the war. Whilst some wished to continue to support the war effort, those who resigned were in opposition to the war and thought the NUWSS should work for peace. Catherine Marshall was among several prominent women in the NUWSS to resign, sending her letter of resignation to Mrs Millicent Fawcett, President of the Society on 3rdMarch 2015:

‘I have come to the conclusion that I cannot remain an officer of the National Union… I feel that the most urgent duty for women, and especially for suffragist women, in this appalling calamity of war that has come upon us is to do their utmost to minimise the disastrous results of war, and to help prepare for a right use of victory if it comes.’ (1)

The minutes of the meeting of the NUWSS Executive Committee held on 18th March 1915 state:

‘Mrs Fawcett said that… Miss Courtney’s and Miss Marshall’s resignations had been based largely on the ground that the Council did not give the leave to work for peace more in the way they desired.… Further, Miss Courtney and Miss Marshall clearly explained that they resigned because the Council had made it evident that it did not wish the National Union to undertake active work on peace lines.’ (2)

In 1915 there were 11 resignations from the Executive Committee arising from disagreement with Millicent Fawcett, long established president of the NUWSS, about the focus of the Society’s activities (3). Such was the standing of Millicent Fawcett that she was not ousted from her position as President and a number of expressions of support for Mrs Fawcett were received.

…I consider that questions of peace and war are intimately connected with Women’s Suffrage

From 1915 Catherine moved towards more pacifist and socialist activities and linked these to her feminist beliefs and values. A letter dated 3rdFebruary 1915 from Catherine Marshall to Mrs Oliver Strachey states:

‘I do not consider it within our province to conduct a campaign on any questions totally disconnected from the Suffrage question, but I consider that questions of peace and war are intimately connected with Women’s Suffrage’ (4).

Catherine’s work during the First World War

Pacifism emerged during the First World War as a movement but there were earlier traditions of resistance, some, but not all, motivated by religion (5). In a 1915 paper, Women and War,Catherine Marshall wrote about her personal perspective (6). It was to be presented at a conference in London but at the time she was ill and unable to give the paper.

Catherine was one of a group who organised the international Women’s Peace Congress, which took place at The Hague in February 1915. She liaised with women from the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany and worked towards obtaining passports for British women who wished to travel and attend the Congress. 120 applied to go but the government, which initially refused to grant passports, eventually agreed to a selection of 20 women chosen by the Home Secretary. Unfortunately, the shipping lanes of the North Sea were closed by the government and so only three British women managed to attend and they did not travel from the United Kingdom. Two were already at The Hague helping to organise the event and one travelled from the United States (7).

Catherine was one of a group who organised the international Women’s Peace Congress, which took place at The Hague in February 1915.

On 11thMay 1915 Catherine Marshall chaired a meeting in Westminster Central Hall in London where there was a report on the Congress by the three delegates who had attended. The delegates voiced appreciation of the British Committee of the Women’s International Congress and especially of Catherine Marshall who had become the Honorary Secretary. The Conference had significance:

‘It was the first international meeting to draw up an outline of the principles needed for a peace settlement to succeed. The Covenant of the League of Nations after the war is remarkably similar to the 20 resolutions passed by the delegates. They included democratic control of foreign policy, with no secret treaties, universal disarmament, future international disputes to be referred to arbitration – and of course, equal political rights for women, and the involvement of ordinary men and women in the final peace conference. Branches of what was to become the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom were set up throughout Europe, the US and other countries, indicative of the desire of many to work internationally.’ (8)

Women’s International League (WIL)

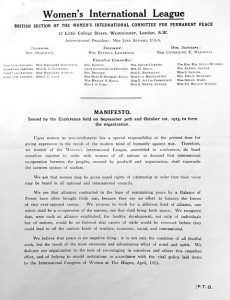

The Women’s International League (WIL) was an international peace movement that grew out of the Women’s Peace Congress. Catherine Marshall was again in a key role as Honorary Secretary for the British branch of the organisation. The WIL Manifesto was issued at their inaugural Conference held on 30thSeptember to 1stOctober 1915:

‘Upon women as non-combatants lies a special responsibility at the present time or giving expression to the revolt of the modern mind of humanity against war. Therefore, we women of the Women’s International League, assembled in conference, do band ourselves together to unite with women of all nations to demand that international co-operations between the peoples, secured by goodwill and organisation, shall supersede the outworn system of values.’ (9)

Catherine’s family in Keswick were interested and showed support for the WIL activities. Caroline Marshall, Catherine’s mother, paid £1.10s subscription plus a donation of £20.00 in 1917-1918. (10)

The WIL’s First Yearly Report (October 1915-October 1916) shows that in its first year the organisation achieved a total membership of nearly 2,500 with 35 branches in addition to Headquarters. (11) However, Catherine resigned however due to her appointment as the Honorary Secretary of the Non-Conscription Fellowship, promising to return. (12)

Catherine resigned her Honorary Secretaryship of WIL in a letter dated 7thNovember 1916 in order to focus more on her work with the No Conscription Fellowship:

‘I have never in my life been so torn in two between work that I love and consider of the most vital importance on either hand. I think the Committee understands that I have made the choice I have made because I am convinced that the conscientious objectors are doing more for the cause the W.I.L stands for than is possible for any other group of people to be doing at the present juncture. The N.C.F stands for something far wider than mere personal refusal to bear arms. I think I have been able to help them in some degree to develop and make good the positive and constructive ideals involved in their attitude about war…. Incidentally, they (the COs) are all becoming ardent Women’s Suffragists.’ (13)

Catherine remained on the WIL Executive Committee and as one of the WIL’s representatives on the International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace.

Women’s International League Manifesto,1915.

Image courtesy of Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle: Ref D/MAR/4/77

Thanks to the UK section of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom for permission to reproduce this image

No Conscription Fellowship (NCF)

In January 1916 Catherine began work for the No Conscription Fellowship (NCF), an organisation unceasingly opposed to war since its formation in the autumn of 1914 by Fenner Brockway and others. In 1915 members issued a common statement expressing their determination not to serve in the military or be involved in war work (14). The NCF provided support to men who resisted conscription and provided to support to conscientious objectors (COs) attending military tribunals or in prison.

To campaign against war and support conscientious objectors took courage.

COs faced often faced harsh treatment and some were force-fed. Over 6,000 spent time in prison. Catherine Marshall initiated the Conscientious Objectors Information Bureau. (15) She also became the acting Honourable Secretary of the NCF when Clifford Allen, Chairman of the organisation, was imprisoned in 1916. Catherine was briefly in a relationship with Clifford Allen. He had been imprisoned three times as a CO and for a short period during the war they lived together in London when neither was in good health. (16)

Catherine’s role in the NCF was acknowledged by H. Runham Brown, in The No Conscription Fellowship: A Souvenir of its work 1914-1919:

‘At the Head Office there was a splendid band of keen and capable women. To our first (November 1915) Convention Catherine E. Marshall came as the Fraternal Delegate of the Women’s International League (for Peace and Freedom). She was so impressed by the spirit there revealed that she decided to devote all of her services to our movement. She became Parliamentary Secretary, and later Acting Hon. Secretary of the Fellowship. It was her determined will that built up the Parliamentary Department of the NCF, so that our stand was never without a champion either in the House of Commons or the House of Lords.’ (17)

Catherine’s role after the First World War

Ill from exhaustion and perhaps from overwork for some of 1917, Catherine was less active but returned to her work to ensure peace. She was a delegate at the Women’s International Congress in Zurich 1919 where many delegates were from countries who had been involved in the war. Catherine went back to being active in WIL after the war. At the 1919 Congress she proposed that the name should be changed to The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) and she worked at the WILPF headquarters in Geneva from 1923-24. In 1923-24 she became an envoy for WILPF, visiting heads of state in France and Germany and workers in the Ruhr who were involved in non-violent resistance. (18)

There is less in Catherine’s archives regarding the interwar period. In the 1930s she was active in a different connection helping people escape from Nazi Germany by housing some Jewish Czech refugees at Hawse End, the house she and her brother Hal owned at Portinscale, near Keswick in Cumbria (19). Although she suffered from ill health during some of this period Catherine was active in the Union of Democratic Control and in the Labour Party in addition to WILPF.

Concluding remarks

Catherine’s peace work demonstrated the organisation and leadership shown in her earlier suffrage work: going out, speaking and enlisting support. She was actively head-hunted to become the Honorary Secretary of WIL (20). In some cases she had a senior position in already established structures such as the NUWSS and NCF; at other times she worked to establish the organisation and create structures. As with her suffrage work there was an adherence to systems and structures and working within constitutions, but she was a leader, an initiator and a team player. She got things done. Jo Vellacott who has written a biography of Catherine notes:

‘Catherine believed in personal contact, and had no reservations about setting up formal and informal meetings with anyone with whom she wanted to talk…’ (21)

Catherine had agency, she had courage and was visionary. She initiated meetings with the prime minister and other politicians such as Phillip Snowden, MP for Blackburn. She networked with people with whom she had existing connections as many of the people active in the peace movement were involved in women’s suffrage and she created and worked towards maintaining new ones.

To campaign against war and support conscientious objectors took courage. The so-called ‘peacettes’ were ridiculed. Her offices were raided. Catherine had the courage of her convictions to ignore ridicule and continue with her work. Whilst the First World War gave a lot of women an opportunity to work in new roles because of the shortage of labour, Catherine’s work challenged traditional women’s roles in a different way because she wanted to work to correct injustices in the world and had a vision of a different future. She worked internationally for transnational benefits.

- Letter from Catherine Marshall to Millicent Fawcett, 3 March 1915. Archive ref: D/MAR/3/45, Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle.

- Minutes of the NUWCC Executive Committee Meeting held on 18 March 1915. Archive ref: D/MAR/3/45, Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle.

- Correspondence from various Executive Committee Members sent to the NUWCC in April 1915. Archive ref: D/MAR/3/45, Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle.

- Letter from Catherine Marshall to Mrs Oliver Strachey, 3 February 1915. Archive ref: D/MAR/3/44, Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle.

- Brock, Peter & Young, Nigel, 1999. Pacifism in the 20th New York: Syracuse University Press.

- Opposing World War One: Courage and Conscience, Fellowship of Reconciliation, Pax Christi, Peace Pledge Union, Quaker Peace and Social Witness, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

- Peace Pledge Union.The Men Who Said No: Women Working for Peace: Catherine Marshall. org/context/women/marshal_c.html.

- Peace Pledge Union. The Men Who Said No: Women Working for Peace: Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. http://menwhosaidno.org/context/women/wilpf.html.

- Women’s International League (British Section of the Women’s International. Committee for Permanent Peace) Manifesto,1915. Archive ref. D/MAR/4/77, Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle.

- WIL Third Yearly Report,1917-1918. Archive ref: D/MAR/4/80, Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle.

- WIL First Yearly Report, 1916.Archive ref: D/MAR/4/78, Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle.

- Letter from Catherine Marshall to Millicent Fawcett sent on 3 March 1915. Archive ref: D/MAR/3/45, Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle.

- Letter from Catherine Marshall to WIL sent on 7 November 1916. Archive ref: D/MAR/4/78, Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle.

- No Conscription Fellowship Collected Records (CDG-b Great Britain), Swarthmore College Peace Collection. https://www.swarthmore.edu/Library/peace/CDGB/No-ConscriptionFellowshp.html

- Assorted documents from Catherine Marshall collection. Archive ref: D/MAR/4/17, Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle.

- Vellacott, Jo, 2004. Marshall, Catherine Elizabeth (1880-1961). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. http:/wwww.oxforddnb.com/view/article/38527.

- Brown, H. Runham, 1919.The No Conscription Fellowship: A Souvenir of its Work 1914-1919. Cited in Opposing World War One: Courage and Conscience, 2013. Fellowship of Reconciliation, Pax Christi, Peace Pledge Union, Quaker Peace and Social Witness, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

- Proceedings of the International Conference of Women Meeting in Zurich, May 12 to May 17 1919. Proceedings of the WIL meeting held in London on October 30 to 31, 1919. Archive ref: D/Mar/4/81, Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle.

- Assorted documents from Catherine Marshall collection. Archive ref: D/MAR/6/1, Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle.

- Letter from Catherine Marshall to Lady Courtney of Penwith, 21 September 1915. Archive ref: D/MAR/4/77, Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle.

- Vellacott, Jo, 2004. Marshall, Catherine Elizabeth (1880-1961). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,Oxford University Press. http:/wwww.oxforddnb.com/view/article/38527.