We wanted to find out how the girls at our school viewed the war and what they did to contribute to the war effort in the local area. The adults’ attitudes and how they projected these views onto the pupils at our school was also very interesting. Overall, life during the war at Lancaster Girls’ Grammar School (LGGS) was different to the modern day in a variety of ways, yet we think their caring attitudes concerning the wider world reflect our own: they may have raised money for Prisoners of War but we still raise money for Children in Need, our house charities and the Camel Library, which delivers books to remote rural schools in Kenya.

How did Lancaster Girls’ Grammar School respond to the war effort during World War 1?

Posted by Ella Tasker and Grace Pollard, with additional research by Daisy Wright, Lancaster Girls’ Grammar School

What did adults encourage?

Henry F. Hibbert, who was the chairman of the Lancashire Education Committee, composed a letter addressed to the boys and girls of Lancashire, which featured in the annual school magazine, The Chronicle of the Lancaster Girls’ Grammar School, in 1917, stating ‘every one of you can help, whatever position you occupy in your school’ (pp. 2-3). This perhaps demonstrates the intention of influential adults in the field of education to promote the values of hard work and the belief that young people could contribute to the war effort. We were surprised to read what sound like feminist views in the letter, for example in encouraging girls to take advantage of ‘the new opportunities open to them’ as ‘their country needed more trained and educated women.’ It is important to consider how this letter may have influenced the students at LGGS, as well as throughout Lancashire. It suggests that the times were indeed ‘strenuous’ but that adults valued the help of young people and needed the next generation to aid those older than themselves.

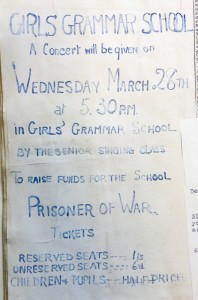

Poster advertising fundraising concert for school PoW, March 1917

LGGS Scrapbook and News Cuttings Book, No.4: p.37

Courtesy of Lancaster Girls’ Grammar School

The Headmistress, Miss Phillimore, also contributed to raising the students’ awareness of the war that raged on around them. Her three brothers were listed as on ‘active service’ alongside the fathers and brothers of various LGGS pupils in the 1915 Chronicle, (p.2) and the death of one of these brothers from ‘wounds received in action’ was announced publicly in the 1916 Chronicle (p.33). This may have served to remind the girls of the harsh reality of war that the propaganda failed to mention and shows how close to home the conflict really was. We found it shocking how harshly this reality was expressed in the Chronicles, especially an introductory letter from the Headmistress to the 1915 Chronicle. Reflecting on the opening of the new school building, Miss Phillimore encouraged the girls to ‘lay the foundations and build the School up,’ stating that:

‘The best foundation is love: i.e. love for your fellowmen and love for all that is good and true and beautiful and wise… If every individual of every nation cherished the feeling in their heart, it is obvious there would be no one left who would wish to fight, so that there could be no more war’ (pp. 1-2).

You might not expect this controversial anti-war opinion to be presented by a teacher to the younger pupils. Yet, after further thought it does remind us of the ethos of LGGS even today, which encourages us to grow into ‘educated’ women who are more aware of the world.

Adult voices appear consistently throughout The Chronicle, which would have been distributed to the majority of families of LGGS students, influencing not only the pupils but also their brothers and sisters. The opinions that the girls were exposed to will have greatly affected their own views and therefore how motivated they were to help the war effort in the local area.

‘If every individual of every nation cherished the feeling (of love) in their heart, it is obvious there would be no one left who would wish to fight, so that there could be no more war.’

What did the LGGS girls do in response?

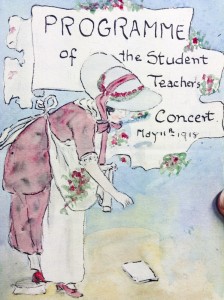

Programme for fundraising concert for school PoW, May 1918

LGGS Scrapbook and News Cuttings Book, No.4: p.40

Courtesy of Lancaster Girls’ Grammar School

The girls here at LGGS had a very active role in the local war effort. This can be seen particularly through their support for Prisoners of War (PoWs). During World War I, many PoWs were aided by their home communities. From February 1917 LGGS sponsored a Prisoner of War named Private Frederick Cooper of the 9th Battalion of the King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment, who was from Royton, near Oldham (The Chronicle, 1918, p.6). Initially, Private Cooper served in France and Flanders, for which he was later awarded the 1914/15 Star. After that, he was moved to Salonika with the rest of the 9th Battalion and it was here he was captured by the Bulgarians in December 1915. It wasn’t until January 1916, however, that he was officially reported missing and then later confirmed to be a Prisoner of War. (1)

In 1917 the school raised a sum of £44, 15 shillings and 2 pence for their PoW through subscriptions from staff, form contributions and fundraising concerts (The Chronicle, 1918: p.5). In early October 1918, the girls received the great news that their PoW had been set free, owing to the truce between the Allies and Bulgaria. The school then decided to adopt another PoW, Lance Corporal W. J. Leather who was at Stammlager in Germany. However, before the pupils were able to send the money that they had raised they received the news that this Prisoner of War had also been repatriated due to the signing of the Armistice on November 11th. The school consequently sent the funds to St. Dunstan’s Hospital for blinded soldiers and sailors. With hindsight, it is amazing what the girls achieved and has inspired us to promote our modern charity fundraising efforts after hearing what our predecessors did.

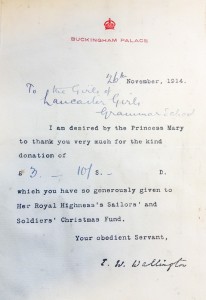

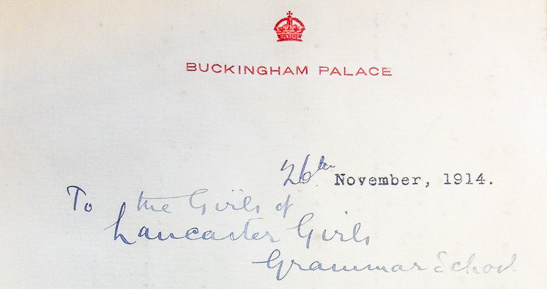

There are other ways that the LGGS girls contributed to the war effort. For example, they raised money for Her Royal Highness’s Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Christmas Fund in 1914, donating £3 and 10 shillings to the fund and receiving a letter on behalf of the Princess Mary thanking them for the money (LGGS Scrapbook and News Cuttings Book, No.4: p.18). On ‘Empire Day’, 24th May 1916, 206 LGGS pupils went to the Tower, Morecambe to see some ‘cinematograph pictures’ called ‘Britain Prepared’ that showed soldiers doing trench work and drill (The Chronicle, 1916, p.4). In the 1918 Chronicle, B. Martin from Form IIa describes how women and girls are ‘doing our bit’ for the war effort (p.27), firstly by taking on the jobs which had previously been perceived as male work, including becoming station porters and even post-women. She also mentions how some have become nurses and travelled to France to support the soldiers. The student encourages the girls at school to do their bit by being helpful at school, careful with paper usage and helping out in the garden, saying that ‘we can do just the same as the women, if we try.’

‘Women all over the country are having unique opportunities to show their mettle.’

An anonymous contributor to the 1916 Chronicle recounts how she helps in the running of her father’s farm (p.16). She writes about the huge lack of young men who used to do the farming, and how, without the crucial help from her and her sister, her father’s farm would not be able to run because of the lack of labourers. She says that the ‘stress’ of wartime means that ‘Women all over the country are having unique opportunities to show their mettle.’

We believe it is also very important to highlight the various other activities that the students were doing, particularly during the earlier years of the war, including hosting tea parties and dances. In fact, looking through editions of The Chronicle, there is a complete lack of information concerning the war at first. Not only did the girls not write about it but there did not seem to be any show of the fear and apprehension that we might expect when so many fathers and brothers went to fight. Instead, The Chronicle continued to describe the usual things that the girls had done before the war, for example sports matches and school trips, including even a holiday to Carlisle.

To conclude, from looking at the materials in the school archives, we can only begin to understand what the girls were living through at this time but the things they did to help their country seem to us to be truly admirable.

… we can only begin to understand what the girls were living through at this time but the things they did to help their country seem to us to be truly admirable.

- Many thanks to the King’s Own Royal Regiment Museum, Lancaster, for providing this information.