The Munitionette’s life was not easy, with long working hours, often living in a strange town, away from family and friends. Popular history has tended to concentrate on the poor working conditions and the sacrifices made by these women. This article gives an insight into other aspects of their lives in World War 1, through the reports in the Lancaster Guardian of the Munitions Tribunal and other court proceedings.

Munitions factories in Lancaster and Morecambe: women’s work on the home front in World War 1

Posted by Christine Workman

Why munitions factories were established in Lancaster and Morecambe

Before August 1914, munitions were made in three government-owned establishments at Waltham Abbey, Enfield Lock and Woolwich. Additional munitions were provided by private contract with trusted companies such as Vickers Armstrong and Cammell Laird. When war was declared munitions production increased in private companies but there was a shortfall that led to the ‘Shell Scandal’ of May 1915. As a result the government passed the 1915 Munitions of War Act. This gave the Munitions Dept., under Lloyd George, far-reaching powers to declare some factories ‘Controlled Factories’, where workers followed stringent rules and could not strike. It could also create ‘National Factories.’

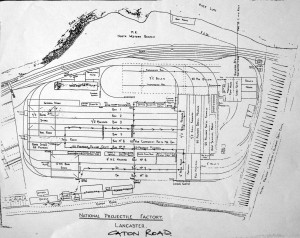

National Projectile Factory, Caton Road, Lancaster, ca. 1917

Image courtesy of www.kingsownmuseum.com

Over 8,700 companies and factories in the UK produced munitions of various sorts during the First World War. However, only 218 were directly administered by the Ministry of Munitions as National Factories. Of these, 170 National Factories were in England, with the balance located in Scotland, Wales and Ireland. Many of the National Factories were adapted from existing works, while others were located in new, specially designed factories. (1) Manufacturing employers were reluctant to employ women because it was felt that they may not have or could not learn the necessary skills, and employers also feared opposition from the unions. The government set an example to private industry by employing mainly women in the munitions factories. (2) Over 700,000 women worked in the munitions industry during the war. (3) They are sometimes called Munitionettes.

Manufacturing employers were reluctant to employ women because it was felt that they may not have or could not learn the necessary skills, and employers also feared opposition from the unions.

The National Projectile Factory (NPF), Lancaster

In October 1918, one month before the end of the war, there were 8,656 employees at the National Projectile Factory (NPF) in Lancaster, of whom 47% were women. Lancaster was the largest NPF in terms of employment; the average was 4,500. There were fewer women employed here, as shell forging was considered to be men’s work. The factory was purpose-built in September 1915, on a site of 33 acres between the River Lune, Caton Road (A683) and Lancaster Canal. Vickers managed both this factory and the National Filling Factory (NFF) at Morecambe for the government. Empty shell cases were manufactured, which were then sent, by rail, to the Filling Factories to be filled with explosives and have the fuse fitted. Altogether the factory produced over two million shells, including: 993,900 6-inch high explosive and chemical shells, 448,000 9.2-inch shells, 9,600 8-inch shells and 589,500 60-pounder shrapnel. During 1919, the factory was turned over to the manufacture of 250lbs. and 500lbs. aircraft bombs. (4) However, it is not known whether women continued to do this work or whether they gave up as was expected at the end of the war, perhaps returning to their former employment. (5

Working conditions

Popular history has focused on the harsh working conditions of the factories: long hours – up to twelve per shift, physically demanding work, danger from explosion and from long-term health conditions caused by the exposure to harmful chemicals, particularly TNT poisoning. (6) The latter could turn hair a ginger colour and the skin yellow, hence the nickname ‘canaries.’ (7) The reality was more complicated. There was an ever-present danger of explosion or fire in munitions factories and there were several explosions, the largest being at NFF Chilwell in July 1918 which killed 134 workers and injured another 250. In October 1917, an explosion at NFF Morecambe destroyed the factory and killed 10 people (see below).

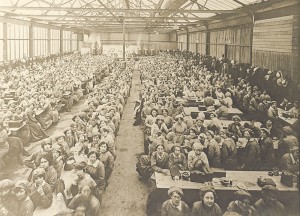

Each National Factory had in-house health care with a doctor and nurse. To ensure good health (and thus increased production) the factories provided canteens for the workers and a recreation room with activities. Purpose-built sites, like Gretna (Explosives Factory) provided housing too. However, there was great variation between the different sites. (8)

Being away from home and family, possibly for the first time, must have been hard for the young women who came from all over Britain. The women were put in lodgings, often some distance from the factory. Sarah Stretch, who was fined £5 in 1917 for possessing matches to light her bicycle lamp, had to cycle four miles to work, often late in the evening. (9)

In October 1918, one month before the end of the war, there were 8,656 employees at the National Projectile Factory (NPF) in Lancaster, of whom 47% were women.

Entertainment in Lancaster for the Munitionettes

At Lancaster, the NPF Social and Athletic Club organised several events for all Vickers workers. At Whitsun, 1917, they organised an amateur sports and carnival in Lancaster. It involved sports competitions, a picnic, stalls, music and, in the evening, a confetti carnival and al fresco dancing. Five thousand people attended. Thirteen female munitions teams, each consisting of eight women, entered the tug-of-war competition. Teams represented different sections of both factories. The women’s final was a keenly fought contest between the ‘canaries’ from White Lund and the NPF ‘nine point twos,’ the latter being the eventual winners. (10) The men also had a tug-of-war competition in which eleven teams participated. A Swimming Gala was held in September 1917. (11)

Women munitions workers in the canteen of the National Projectile Factory, Lancaster.

Image courtesy of Lancaster City Museum

The Khaki Club

In October, 1916, the YMCA in China Street began a Munition Workers’ Club. (12) It had been a Khaki Club for the army and navy the previous winter. The YMCA Committee set up the Club in view of ‘the large influx of munition workers to the district’ and ‘Games, refreshments, [and] musical evenings’ were provided for them in their leisure hours. (13) A Ladies’ Committee was set up to organise catering for each evening in the week. Very little is known about this Club or a sister ‘hut’ that was set up in Skerton in 1917 for women munitions workers on that side of the river. Organised by the Church Army, it was located on the lawn of Skerton Vicarage and had a café with space for games and writing letters. (14) For an insight into other aspects of the lives of women munitions workers, see The Trials and Tribulations of the Lancaster/Morecambe Munitionettes.

Mary Agnes Wilkinson, a telephonist at the Exchange in Cable Street, Lancaster, was awarded the British Empire Medal as she ‘rendered invaluable service… proceeding to her post through the danger zone at grave personal risk,’ despite being blown off her bike twice en route.

The National Filling Factory (NFF) No. 13, Morecambe

There was a greater proportion of women employed at the National Filling Factory (NFF), Morecambe, than at the NPF in Lancaster, being 64.4% of the 4,621 employees in September 1917. Construction of the National Filling Factory at White Lund, Morecambe, began in November 1915 on a 400 acre site. The site needed to be so large because explosive safety was a key issue and the site used parallel production facilities in separate small, wooden huts to reduce the risk. The NFF filled a range of shells with Amatol, a mixture of TNT and ammonium nitrate, but they also produced gas shells. Vickers produced filled shells for only 15 months before the site was almost entirely destroyed by fire and an explosion. (15)

The White Lund Explosion, 1 October, 1917

The fire started at around 10.30 pm on the upper floor of Unit 6c, which contained large amounts of TNT. The lower floor contained 12-inch shells, partly filled. These exploded after about 20 minutes. (16) The largest explosion of ammunition occurred four and a half hours after the initial fire. Ten people, all male, mainly firemen, were killed. Casualties were low because the workers were in the canteen (connected to the charge house) on their evening supper break and they were able to escape. 300 women were helped out of the charge house by Policeman J. Johnson. There was some panic and a general rush for the gates and women were reported as moaning and screaming. Some ran through the gate on the Lancaster side and fell into the flooded marshes before being rescued. (17) Others scrambled through the barbed wire enclosures. Eight women were reported missing the next day. They had feared for their lives and gone back to their homes in other Lancashire towns. An account by Anne Spencer, aged about 11 at the time of the explosion, described how people gathered at the old pier on the seafront and watched exploding shells go over them. The windows had been blown out of the back of their house in Morecambe and shrapnel was found several miles away. She had seen the girls who worked at the factory running ‘terror stricken past our house. My mother tried to persuade some of them to come into the house but they were much too scared.’ (18) Some were said to have run as far as Kendal.

Several acts of bravery were subsequently rewarded. Mary Agnes Wilkinson, a telephonist at the Exchange in Cable Street, Lancaster, was awarded the British Empire Medal as she ‘rendered invaluable service… proceeding to her post through the danger zone at grave personal risk,’ (19) despite being blown off her bike twice en route. (20) Four men were awarded the Edward Medal for their bravery including Thomas Kew, a train driver, and Abraham Graham, who shunted 49 ammunition trucks holding 250,000 live shells out of the danger zone to prevent further explosions. (21) It took three days to secure the site. The factory never re-opened. Workers were paid off and given a fortnight’s extra wages. We do not know what happened to the women workers after this.

- Kenyon, David, 2015. First World War National Factories: an archaeological, architectural and historical review. Historic England Research Report Series, 076-2015, pp.6-11

- Walsh, Ben, 2009. AQA GCSE Modern World History. 3rd ed. London: Hodder Education, p.302.

- Simkin, John, 2014. Munitionettes [online]. Available at: http://spartacus-educational.com/Fmunition.htm

- Pastscape, 2015. Lancaster National Projectile Factory [online]. Available at: https://pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=1574435&sort=4&search=all&criteria=Lancaster%20munitions&rational=q&recordsperpage=10

- Walsh, Ben, 2009. AQA GCSE Modern World History. 3rd ed. London: Hodder Education, p.353. For more information about what happened to the NPF site after the First World War, see Lancaster Civic Society’s Guides to Lancaster, No. 30: Lancaster Wagon Works, Caton Road. Available at: http://www.lancastercivicsociety.org/

- Clements, Kate, 2016. 9 Women Reveal The Dangers Of Working In A First World War Munitions Factory [online]. Available at: http://www.iwm.org.uk/history/9-women-reveal-the-dangers-of-working-in-a-first-world-war-munitions-factory

- Storey, Neil R. & Housego, Molly, 2010. Women in the First World War. Oxford: Shire Publications, p.41.

- Kenyon, David, 2015. First World War National Factories: an archaeological, architectural and historical review, Historic England Research Report Series, 076-2015, pp.25-35.

- Lancaster Guardian, 27 January 1917, p.3, c.6.

- Lancaster Guardian, 2 June 1917, p.6, c.3.

- Lancaster Guardian, 22 September 1917, p.6, c.3.

- Lancaster Guardian, 14 October 1916, p.5, c.6.

- Lancaster Guardian, 14 October 1916, p.5, c.6.

- Lancaster Guardian, 13 October 1917, p.7, c.5.

- Kenyon, David, 2015. First World War National Factories: An archaeological, architectural and historical review, Historic England Research Report Series, 076-2015, p.18.

- Nuttall, Thomas, c.1917. Report on explosion at White Lund Munitions Factory, Morecambe, 1917. Held at Lancashire Record Office, Preston: Ref DDX 3059.

- Morecambe and Heysham Visitor and Lancaster Advertiser, 29 September 1937.

- Spencer, Anne, 1969. World War 1. Explosion at the National Filling Factory, White Lund, started on October 1st, 1917. Childhood memories of this event by Anne (‘Nan’) Spencer, née Harrington [online]. Available at: http://www.heyshamheritage.org.uk/AnnsStoryLR.pdf

- 1918 New Year’s Honours List.

- Lancaster Guardian, 26 September 2007. Available at: http://www.lancasterguardian.co.uk/lifestyle/nostalgia/white-lund-explosion-1-1170802

- For further information on the Edward Medal recipients, see Lancashire County Council, 2014. News: The Edward Medal comes home [online]. Available at: http://www3.lancashire.gov.uk/corporate/news/press_releases/y/m/release.asp?id=201408&r=PR14/0390